Drought Conditions Worsen in East Africa A Deepening Regional Crisis

A devastating climate emergency is unfolding across East Africa as prolonged drought conditions intensify, threatening the survival of millions and destabilizing fragile communities. From Ethiopia’s highlands to Kenya’s arid northern counties and Somalia’s war torn countryside, the region is experiencing one of its worst drought episodes in decades. After successive failed rainy seasons and increasing heat extremes, water sources are drying up, crops are withering, livestock are dying, and hunger is deepening. What began as a seasonal dry spell is now evolving into a full blown humanitarian and environmental catastrophe.

1. The Anatomy of the Current Drought

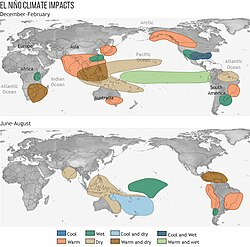

The ongoing drought in East Africa is not a single, sudden event but the culmination of five consecutive failed rainy seasons across large portions of the region. The “long rains” (March to May), which are crucial for crop production and livestock grazing, have become increasingly erratic, both in timing and intensity. In 2025, much of Ethiopia, northern Kenya, and southern Somalia received less than half of their average rainfall, leading to severe soil moisture deficits. Meteorologists attribute this trend to a combination of climate change induced warming in the Indian Ocean and shifting atmospheric patterns, including the influence of a weakening La Niña and the formation of a neutral to warm ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation) phase.

These changes have not only reduced precipitation but have also increased temperatures across the region, accelerating evapotranspiration and placing additional stress on already scarce water resources. Rivers that once supported villages and farms are now seasonal trickles or completely dry. Boreholes are running dry or producing saline water, and the once dependable seasonal rainfall that sustained agriculture has become unreliable and dangerously inconsistent.

2. Agricultural Collapse and Food Insecurity

The East African economy, particularly in rural areas, is heavily reliant on rain fed agriculture. With rainfall disappearing, crop production has plummeted across the region. In Ethiopia, teff and maize harvests have declined by more than 30% in some districts, while Kenya’s maize growing Rift Valley is reporting its lowest yield in over a decade. Somalia, already struggling with the effects of political instability and conflict, is experiencing near total crop failure in many provinces, compounding the effects of food scarcity.

As a result, food prices have skyrocketed across markets. In Nairobi, for example, the price of staple items like maize flour, beans, and cooking oil has nearly doubled since January. For families who live on less than $2 a day, these price hikes are catastrophic. According to recent assessments by local NGOs, over 23 million people across the region are facing acute food insecurity, with many already resorting to extreme coping strategies like skipping meals, pulling children out of school, or selling off livestock at distress prices.

3. Livestock Deaths and the Collapse of Pastoralism

For many communities in East Africa, particularly among nomadic pastoralists, livestock is both a source of food and wealth. In northern Kenya, southern Ethiopia, and central Somalia, herders are facing the brutal consequences of the drought as grazing land disappears and water points dry up. Tens of thousands of animals goats, sheep, camels, and cattle have died from starvation and dehydration in just the past three months. Those still alive are emaciated, producing little milk, and are no longer viable for sale or sustenance.

The implications go beyond individual loss. Entire communities whose livelihoods revolve around animal husbandry are facing cultural and economic extinction. Once self reliant, many have now been forced into displacement camps in search of food aid and medical support. In pastoral societies where wealth is measured in livestock, the loss of animals has led to a silent but powerful trauma eroding identity, dignity, and social structures.

4. Water Scarcity and Public Health Emergencies

As the drought persists, water scarcity has become a crisis of its own. In many towns and villages across Turkana (Kenya) and Afar (Ethiopia), families must walk 10 15 kilometers daily just to fetch a few liters of water often from polluted sources shared with animals. The burden of this task falls disproportionately on women and children, increasing risks of gender based violence, school dropouts, and long term health issues.

Moreover, poor sanitation and lack of clean drinking water are fueling outbreaks of waterborne diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and typhoid. Health clinics, already under resourced, are overwhelmed with cases of malnourishment and dehydration. In southern Somalia, at least three rural clinics have closed in the past month due to lack of supplies, putting thousands at further risk. The convergence of hunger, thirst, and disease paints a grim picture, especially for children under five and pregnant women, whose nutritional needs are critical.

5. Displacement, Migration, and Social Unrest

The environmental pressure created by the drought is also triggering large scale internal and cross border displacement. In Ethiopia alone, more than 1.5 million people have been forced to leave their homes since January due to water and food shortages. In Somalia, the number of displaced families in the central regions has tripled, many seeking refuge in overburdened camps near Mogadishu and Baidoa. As more people move into urban slums or informal settlements, tensions over scarce resources especially water are rising.

Furthermore, resource scarcity has reignited conflict between communities, particularly over water points and grazing land. Armed clashes between herder groups in Kenya and Ethiopia have already resulted in deaths and displacement. In some areas, the drought is not just a climate crisis it is a security threat, adding fuel to existing ethnic tensions and political instability.

6. Humanitarian Response and Gaps in Aid

Though international aid agencies and local governments have ramped up emergency responses, the scale of the crisis has outpaced available resources. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) recently reported a major funding gap in its East Africa drought response plan less than 35% of required funds have been secured. Food distributions are being delayed or scaled down, and many water trucking services are being suspended due to lack of fuel or maintenance.

Local initiatives, including community water projects and farmer cooperatives, are trying to fill the gap, but chronic underinvestment in infrastructure has left them vulnerable. While solar powered boreholes and drought tolerant crop programs offer promise, their scale is still too limited to meet the growing need. Long term adaptation remains underfunded, and policy responses are often fragmented across borders.

7. Looking Ahead The Case for Climate Resilience

East Africa’s deepening drought crisis is a clear sign of how climate change is reshaping humanitarian and development challenges. What was once an occasional hardship is now becoming a structural threat to life, livelihoods, and national stability. The region urgently needs a two pronged strategy robust emergency response to save lives today, and bold climate adaptation investments to safeguard the future.

This means scaling up early warning systems, supporting climate smart agriculture, investing in water infrastructure, and strengthening regional cooperation on transboundary resource management. Above all, the international community must recognize that climate vulnerable regions like East Africa are not passive victims, but places where proactive partnerships, indigenous knowledge, and sustainable technologies can offer a path forward if supported in time.

Related Post

Popular News

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

No spam, notifications only about new products, updates.